"Lesser Evils" Are the American Way: A Brief History of Voting in the US

Spoiler alert: this longstanding election rationale has failed to stop evil...

The 2024 election is here, which means millions of Americans will choose between “choices” that inspire "dread," “anxiety,” and “frustration.” While many voters are cult of personality diehards, millions more feel they have no choice but to vote for a "lesser evil" even as they express frustration at their meager electoral options.

It's easy to look at current affairs and long for a time when the constitutional system provided better options and didn’t leave people debating which politician was “less” or “more” evil.

A deeper view of history shows such a time scarcely existed.

Et tu, Jefferson?

Many Americans view the start of the 19th century as a golden era in constitutional government. The “founding fathers” were still alive, and they were very much leading the new nation. But it was not a harmonious utopia.

In the election of 1800, Alexander Hamilton, a federalist, believed his party needed to save the country from the "fangs of Jefferson," an anti-federalist. As beloved as Jefferson was then and remains today, many at the time disapproved of his ideology and platform.

Despite this, Hamilton changed his mind amid the stand-off between Jefferson and Aaron Burr. Hamilton wrote to a Massachusetts congressman, "In a choice of Evils let them take the least–Jefferson is in every view less dangerous than Burr." Hamilton believed Jefferson's opposing ideology to be less evil than Burr's selfish motivations for seeking the presidency.

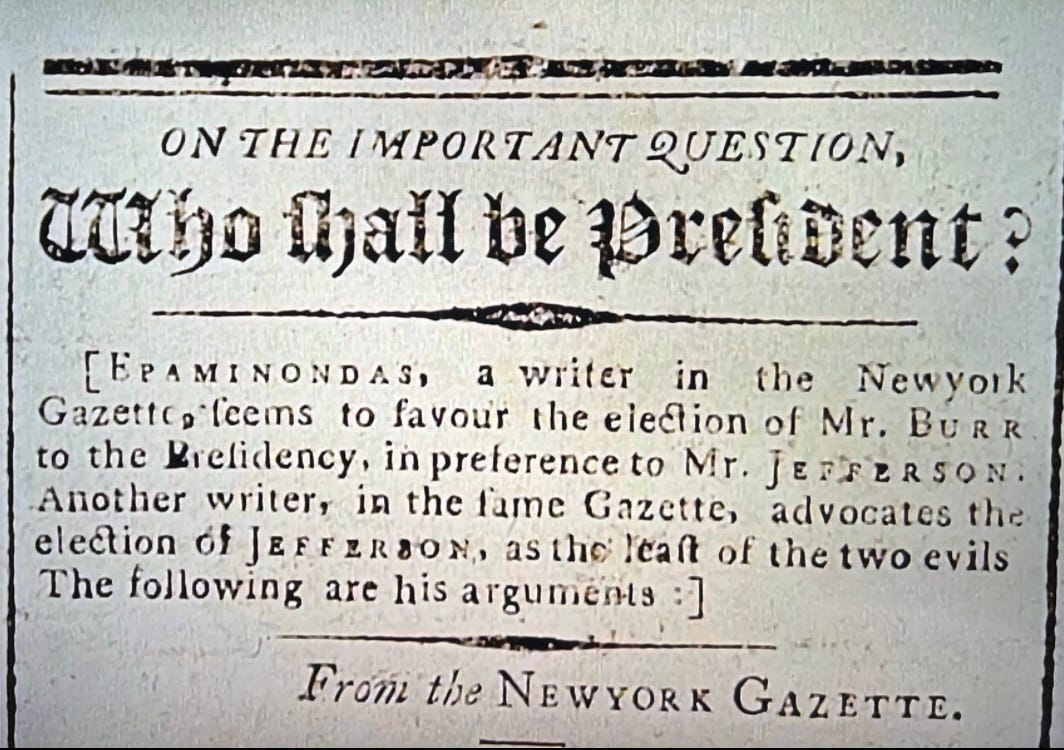

The lesser evil argument was not unique to Hamilton. A newspaper clipping featured in Ken Burns's Jefferson documentary expressed the same sentiment. The op-ed argued that Jefferson was "the least of two evils." If even Jefferson was considered a lesser evil, where does that place Harris, Trump, and America's uniparty?

My (a)political leanings align far more with Jefferson’s (who was not without his hypocrisies and contradictions, including violating the Constitution) than Hamilton’s. However, that Hamilton felt he had to abandon his principles so early on in the history of the country—all in order to save it—reflects a fundamental flaw of government. In this case, it is the tendency of corrupt, power-hungry people like Aaron Burr to seek authority over others.

But this was not a one-off “lesser evil” battle. I recently dove into digitized newspaper archives for presidential election years (and other primary and academic sources) and found that as far back as 1808, nearly every single election saw references to—and arguments in favor of—choosing lesser evils.

The 1808 presidential pick for the Democratic-Republican party was “reduced…to a choice of evils” between Virginia Governor George Clinton and James Madison, who went on to win. By 1812, Madison one author considered Madison “the worst of all possible evil” and longed for a lesser one to choose.

In 1824, well-known politician Henry Clay opted for John Quincy Adams over Andrew Jackson: “I consider that whatever choice we may make will be only a choice of evils,” he acknowledged. In 1928, William Henry Crawford, another politician, preferred Jackson as a lesser evil to Adams. He expressed as much in a letter to Martin van Buren and surmised Van Buren felt the opposite and favored Adams as the lesser evil. Others also grappled with choosing a lesser evil that year.

By 1832, Jackson and his tariffs were a lesser evil to some voters than the risk of nullification over them. Jackson went on to declare he had a right to use the military to crush tariff nullification, and he had already begun forcibly removing indigenous people from their homelands.

Expecting a Different Result?

Beginning in 1824, people made the “lesser evil” arguments in every single presidential election year I reviewed. During every election cycle, newspapers published opinions referring to lesser evils to justify voting decisions. Writers also applied the argument to policies like tariffs, abolition, monetary policy, and war, and the mentality spanned local, state, and federal elections and primaries.

As the slavery question grew increasingly contentious, calls to settle for lesser evils continued. In 1844, the “lesser evil” was called “the positive good.” In 1860, some Southerners regarded civil war as the lesser evil compared to a Republican (Lincoln) victory. However varied the opinions, “lesser evils” often drove voters’ decisions.

Just as today, people often felt they had no choice but evil, which ironically contradicts the notion of elections: they are supposed to reflect choice and agency, yet voters have felt for generations that there is no real choice to be made.

And just as today, no one could agree on what the lesser evil was. Throughout the years, some believed it was Democrats, while others were certain it was Republicans.

In 1896, one voter wrote of William Jennings Bryan versus William McKinley, “A free coinage president appears to me a lesser evil than a stock exchange president.” One writer noted the pervasiveness of the lesser evil mentality in the other direction: “And there are those in plenty who are saying that McKinleyism is the lesser evil, therefore accept that.”

As some “sound money” Democrats declared, they would “accept the lesser of the two evils in the present political emergency, and vote for McKinley, not that we like Republicanism more but Bryanism less.” [emphasis added] Another familiar “rationale.” In another iteration, imperialism was a lesser evil than a lack of sound money, observed a senator in favor of McKinley. Others thought the opposite (as noted by someone who chose McKinley).

Evil aside, this subjective assessment of what constitutes it suggests that one ruling authority can’t possibly uphold and represent the conflicting views and values of the masses.

That hasn’t stopped voters from attempting to preserve the system, which one writer accurately summarized in 1924. Speaking of postal clerks seeking to defeat Republican Calvin Coolidge, one author acknowledged a reality in the “choice of two evils” that remains today: “…in beating Coolidge they may vote for another servant of Wall Street on the Democratic ticket who will make nice promises but nevertheless obey orders from the owners of this country just as well as Mr. Coolidge.”

‘Duty-bound to evil’

Just as today, voters with the lesser evil mentality demanded others fall in line and choose evil. “When the choice is between a greater and lesser evil, duty requires that we should take the lesser,” reasoned one person in 1884. “You are bound to choose the lesser evil in order to defeat the greater,” wrote another in 1892. “It is every citizen’s duty to accept the lesser of two evils,” asserted a concerned voter during the election of 1900. So say people today.

“One has to make a choice of evils when the only chance is to cooperate with the two organizations that absorb the politicians, and we do not fall into the ranks of a party when we prefer it as the lesser evil,” one author clarified in 1876. And yet those parties remained dominant. Evil, as assessed by voters in every era, has continued to prevail.

This “lesser evil” rationale thrived in virtually every election. Even presidents now beloved and considered heroes and visionaries (or villains) were considered “lesser evils” in their time. Many believed Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, and Franklin Roosevelt to be “lesser evils,” while others were sure they were the greater.

“Of two evils, choose neither” - C.H. Spurgeon

Despite the pervasiveness of this argument then and now, there were always people refusing to fall in line.

By 1848, Senator Charles Sumner wrote of the "old political saw, that 'we must take the least of two evils.'" Between Whig Zachary Taylor and Democrat Lewis Cass, Sumner preferred neither. Unsurprisingly, no one could agree on what was the greater evil: Some believed it was Taylor, others Cass. By these assessments, evil won with Tyler, but it would have been victorious had Cass won, too.

Also in 1848, one writer scathingly rejected the lesser evil argument: “The least of two evils never yet gave anything but transitory comfort, while at the same time it treacherously aggravated those symptoms which necessitated future compromises.” And here we are today.

In 1936, one writer succinctly pointed out that “we salve our consciences with the argument that we chose the lesser of two evils, but do nothing to destroy the basic evil.”

In 1956, black rights activist W.E. DuBois famously shattered the lesser evil argument in an essay explaining why he wouldn't vote for Dwight Eisenhower or Adlai Stevenson. Frustrated with the duopoly's refusal to address black rights, he wrote:

"I believe that democracy has so far disappeared in the United States [and] that no 'two evils' exist. There is but one evil party with two names, and it will be elected despite all I can do or say."

This assessment of the two-party system remains accurate.

Today, many Americans feel this way in the face of openly corrupt and authoritarian candidates who don't represent them. They will vote third-party or not at all.

Between the lines of history

The question in this historical rabbit hole is not about which evil is truly "lesser" or even what constitutes "evil." From the time of the "Founding Fathers," now elevated to popular mythology, people couldn't agree on which person or party was the lesser or greater evil. This points to the inherent flaws of the system. For over 200 years, people have been arguing that choosing evil is their moral duty and only choice. Today, it is often called “pragmatism.” Well-intentioned people hoping to disempower evil have argued in favor of this strategy in nearly every election in US history. As many prescient dissenters warned throughout the years, doing so failed to stop evil.

Millions of Americans believe Trump is the lesser evil compared to Harris and vice versa. They are all certain of their opposing conclusions and don't consent to the rule of the candidate they view as the greater evil. With every election cycle, the evil festers—as it has from the outset of this country. Even so, people continue to rely on lesser evil elections in the hopes of mitigating evils they can't even agree upon.

What is apparent to me is that a government intended to remain limited while protecting freedom and civil liberties is nearly $36 trillion in debt, riddled with corruption, mass surveillance, and brazen violations of the Constitution, and beholden to military-industrial bloat and violence. Voting for evil did not work.

The more pertinent question is not about the definition of evil but how much longer people will subscribe to a system that perpetually produces some kind of evil and helps it rise to the top—and what the alternatives could be.

I won't pretend to have all the solutions, though I have some ideas. I don't expect people to stop choosing lesser evils any time soon. The stakes are high, and people feel they have no choice. In light of this, it seems a sufficient step forward on this topic, for now, is to start questioning the ideological foundations of a system that, from its inception, has not only rationalized lesser evils but in doing so also perpetuated evil for generations.

Maybe the greater evil is not one political party or side but the underlying authority that allows one side to forcibly rule over the other without their consent.

I will leave you with a 1904 objection to America’s dominant belief in voting for evil:

“Just so long as you keep on ‘choosing the lesser of two evils,’ you will have nothing but two evils to choose between.”